- If it is not central to the plot, do not include it.

- If you must include it, change the plot.

- Every chapter is its own story.

- Tight, clean book. (There will be foul language as it is about Luther, peasants, and mercenaries. Clean here means clutter free.)

- Keep the goals of the book ever in mind.

- Do not explain. Rather, let the characters live the story. If you must explain, let the characters do it for you.

Category: Workshopping a Novel. “The Hundred: A Novel of Young Luther and His World”

Workshopping Chapter 1

The Hundred: A Novel of Young Luther and His World

As noted when I posted the Preface, I am putting provisional chapters of my novel out there as I work toward finishing this book. There are numerous problems I’ll need to overcome with these working drafts. Feedback on drafts of my non-fiction has been useful; I expect similar results from feedback on fiction drafts. Two writers’ groups are workshopping drafts. Through Scribd, the public will also have access to the work as it happens. I appreciate any and all feedback. It probably goes without saying, but please be polite.

Two Notes:

- This chapter and Chapter 2 may be switched in order in the final manuscript.

- Working covers are only visual aids at this point, but feedback on those is welcome as well.

Purposes of a Public Approach to Drafting a Work of Fiction:

- To generate feedback on drafts.

- To allow those with an interest in the book to watch it unfold.

- To open Luther’s world for the curious.

- To motivate me to finish a project that has driven my academic research for a number of years.

Workshopping a Novel: Preface.

The Hundred: A Novel of Young Luther and His World

- To generate feedback on drafts.

- To allow those with an interest in the book to watch it unfold.

- To open Luther’s world for the curious.

- To motivate me to finish a project that has driven my academic research for a number of years.

Getting A Novel Done

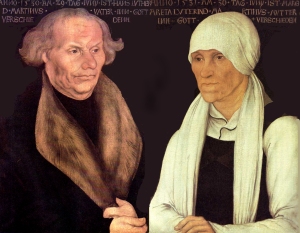

After several requests and 9 years, I have finally created an ebook version of my first novel. The ebook came about while I was working on a model for finishing my second novel, The Hundred, which is about the world of Martin Luther’s youth. It is the first of two novels about Luther and his world, both of which are fairly well drafted.

A few considerations weigh on my production of the Luther novels:

- fulfilling a promise to people who are waiting for them.

- exploring the idea of the novel as a medium for public history.

- getting them done.

I am toying seriously (Can one do that?) with the idea of publishing polished but not final drafts of chapters on Scribd, which houses a few of my older academic papers. These chapter drafts would allow readers to be part of the process as I write, offering feedback and observing the work’s progress. They would provide the public with immediate access to the late medieval world in short snapshots. Publicly available chapters might also stimulate interest in the project before it comes out as a bound book. These drafts would also break down the colossus that is the project at present. Feedback, even if only in page hits, would provide immediate incentive to get through this first book in the next year or two. This sort of motivation and encouragement will become increasingly important given that I will be teaching 3 courses this summer and 4 in the fall.

I welcome comments on this idea.

Darkness

I am often struck by how very black and alive the darkness used to be. Lately I have been waking in the middle of the night. Nightmares, which so rarely visit me, have been a constant in recent days. Waking to a house that is never entirely without light because of nearby streetlights, I am reminded how very dark a moonless night must have been five hundred years ago.

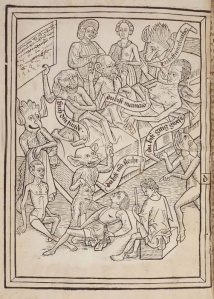

In a world as full of demons as of people, fraught with “quotidien violence” as Julius Ruff describes it, and constant threats of war and deadly illness, the dark was very frightening indeed. One always had to be on one’s guard, even in the moment of death, as here demons tempt the dying.

In a world as full of demons as of people, fraught with “quotidien violence” as Julius Ruff describes it, and constant threats of war and deadly illness, the dark was very frightening indeed. One always had to be on one’s guard, even in the moment of death, as here demons tempt the dying.

Johan Huizinga described the late medieval world beautifully:

“The contrast between silence and sound, darkness and light, like that between summer and winter, was more strongly marked than it is in our lives. The modern town hardly knows silence or darkness in their purity, nor the effect of a solitary light or a single distant cry.

“All things presenting themselves to the mind in violent contrasts and impressive forms, lent a tone of excitement and of passion to everyday life and tended to produce that perpetual oscillation between despair and distracted joy, between cruelty and pious tenderness which characterize life in the Middle Ages.”

How different this is from the homely coziness of modern lamplit rooms late in the evening. It is almost impossible to imagine living with such unlovely companions as the demons above. How bizarre this seems to us, but people found ways to deal with darkness.

My favorite medieval response to night and the fears that haunted it comes from Martin Luther:

“Almost every night when I wake up, the devil is there and wants to dispute with me. I have come to this conclusion: When the argument that the Christian is without the law and above the law doesn’t help, I instantly chase him away with a fart.”

Luther the Challenge

This is why I like him, of course. It is why I have always liked him. Luther’s story is an exquisite challenge to write. It is all too easy to see him as a villain or traitor in the Peasants’ War of 1525. This is precisely how my fictional characters see him. Telling their side of the story is easy.

Telling Luther’s side is not so simple. Martin Luther is not duplicitous. He is not a traitor. But he is dangerously unclear in the years and months before the revolt of 1525, leading the peasants to believe that he will support their cause. Tragically, he makes himself indisputably clear only when he calls for the peasants’ annihilation.

- to keep Luther clear for my reader even while he befuddles his own audience.

- to ensure that he comes across as who he is, for he was not a traitor.